Introduction

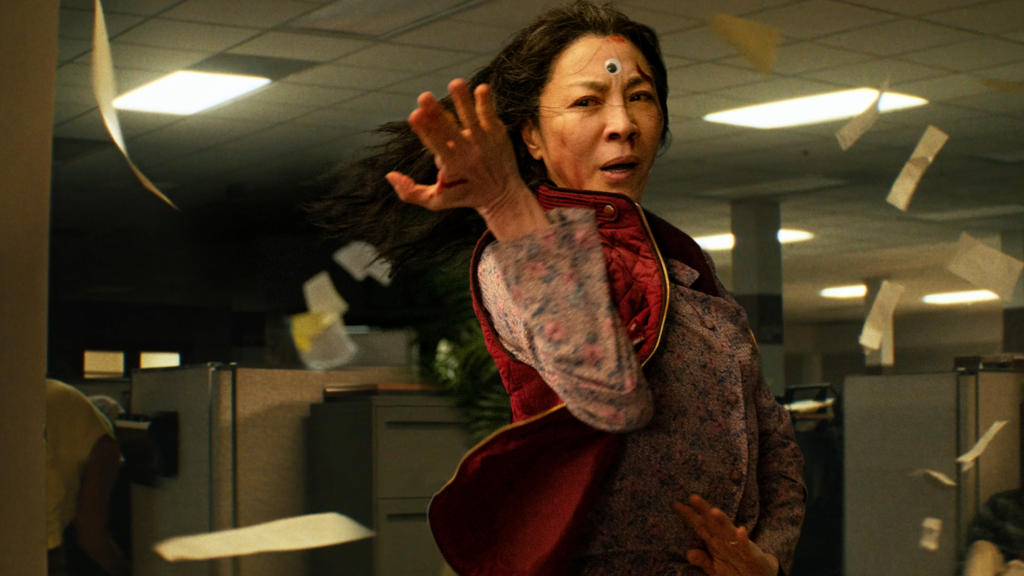

Under the fluorescent lights of the IRS office, Evelyn Wang, buried under receipts and paperwork, is overwhelmed by her failing marriage, disappointed father, and struggling business. In this moment, she embodies a particular kind of cognitive experience that millions recognize intimately: the ADHD mind. The manic pacing and sensory overload of Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022) has resonated powerfully with audiences who have ADHD, not merely as entertainment but as representation. More significantly, the film offers a radical thesis: control isn’t found by forcing rigid structure, but by channeling the very tendencies society labels as deficits to find your own power within the chaos.

ADHD and the Experience of “Everything Everywhere All at Once”

ADHD is characterized by persistent patterns of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that interfere with functioning or development (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). However, clinical definitions often fail to capture the sense of being perpetually overwhelmed by stimuli, the difficulty in filtering relevant from irrelevant information, and what researchers have termed “time blindness” (Barkley, 2012).

The film’s very title encapsulates this experience. Evelyn doesn’t merely face multiple problems sequentially. She confronts them simultaneously, with equal urgency. Her inability to prioritize effectively is a hallmark symptom of ADHD executive dysfunction. The film’s director Daniel Kwan has publicly discussed his own ADHD diagnosis and how it influenced the film’s creation, stating in interviews that the overwhelming, maximalist aesthetic wasn’t just a stylistic choice but an authentic representation of how his mind processes reality (Kwan & Scheinert, 2022).

The multiverse structure itself mirrors ADHD attention patterns. Just as Evelyn’s consciousness cuts between universes mid-conversation, people with ADHD describe their attention as fragmenting across multiple thoughts, memories, and stimuli simultaneously. Dr. Edward Hallowell, a leading ADHD researcher, describes this as having “a Ferrari engine for a brain, with bicycle brakes,” tremendous processing power without adequate regulatory control (Hallowell & Ratey, 2011, p. 45). The film visualizes this exactly: Evelyn possesses extraordinary potential across infinite variations, but lacks the ability to regulate which universe receives her focus.

The Conventional Approach: Structure, Routine, and Suppression

Traditional ADHD management emphasizes external structure and routine. Clinical approaches often focus on compensatory strategies: planners, reminder systems, medication to increase focus, and behavioral modifications designed to help ADHD individuals function within neurotypical frameworks (Barkley, 2015). While these tools can be valuable, they operate from an underlying assumption that ADHD traits are deficits to be minimized, chaos to be contained.

This philosophy manifests in Evelyn’s initial world. Her husband Waymond, gentle and procedural, represents conventional wisdom. He wants Evelyn to focus on one thing at a time, to follow the process, to work within established systems. The IRS office, with its forms and filing requirements, demands exactly the kind of sustained, detailed attention that ADHD makes difficult. Evelyn is failing precisely because she’s trying to operate within structures designed for minds that work differently than hers.

The film’s antagonist, Jobu Tupaki, represents what happens when an ADHD mind is pushed to extremes of overstimulation without support or acceptance. As Evelyn’s daughter Joy, transformed by Alpha Waymond’s experiments into experiencing too much across too many universes simultaneously, she becomes nihilistic. The “everything bagel” of absolute chaos becomes a void of meaninglessness. This mirrors the experience many with ADHD describe: when the demands for normal functioning become too overwhelming, shutdown and depression often follow (Knouse et al., 2013).

The Paradigm Shift: Working With Chaos

The film’s turning point occurs when Evelyn stops trying to impose order and instead learns to harness her natural ability to be everywhere at once. Rather than focusing harder on one universe (the conventional ADHD advice to “just pay attention”), she learns to access multiple universes simultaneously, to leverage the very fragmentation that seemed like weakness.

This mirrors emerging research on ADHD strengths. While ADHD has real challenges, recent neurodiversity-informed approaches recognize associated advantages: creativity, hyperfocus on engaging tasks, ability to make novel connections between disparate concepts, and exceptional crisis response (White & Shah, 2011). Dr. Lara Honos-Webb’s work on the “gift of ADHD” argues that the same neurological differences that create executive function challenges also enable unique cognitive capabilities, particularly in creative problem-solving and divergent thinking (Honos-Webb, 2010).

Evelyn’s ultimate power comes from “verse-jumping,” rapidly switching contexts to access specific skills or knowledge. This isn’t despite her chaotic mental state but because of it. Her mind’s natural tendency toward fragmentation, when accepted rather than suppressed, becomes tactical flexibility. She defeats opponents not through sustained focus on a single fighting style, but by fluidly shifting between hundreds of them, accessing whatever each moment requires.

Many ADHD individuals discover that their productivity and effectiveness peak not when they force themselves into rigid routines, but when they design systems that accommodate natural variability. Research on ADHD and entrepreneurship finds that many successful entrepreneurs credit their ADHD with enabling them to manage multiple projects, pivot quickly, and make creative connections others miss (Wiklund et al., 2017).

Rejecting Routine, Embracing Flexibility

The film’s resolution doesn’t involve Evelyn learning to focus on one universe or establishing a stable routine. Instead, she learns to be intentionally everything everywhere all at once, making flexibility and rapid adaptation her operating system rather than a bug to fix.

When Evelyn finally confronts Jobu Tupaki, she doesn’t defeat her through superior force or focus. Instead, she out-chaoses chaos itself, meeting Jobu in every universe simultaneously, responding to each version with presence and acceptance. The fight becomes a dance becomes a conversation becomes reconciliation. Evelyn wins by embracing the fundamental unpredictability of existence rather than trying to control it.

This represents a profound reframing for ADHD. What if the goal isn’t to become more neurotypical, but to become more skillfully neurodivergent? The film suggests that Evelyn’s power doesn’t come from learning to focus despite distractions, but from developing meta-awareness of her distributed attention and learning to use it strategically.

Practically, this aligns with ADHD management strategies that emphasize working with natural rhythms rather than against them. Rather than fighting the ADHD tendency toward novelty-seeking, build novelty into work through project rotation. Rather than forcing sustained attention to boring tasks, use the ADHD capacity for hyperfocus on engaging challenges. Rather than treating distractibility as pure deficit, recognize it as sensitivity to environmental cues that can enable rapid response to changing conditions (Ashinoff & Abu-Akel, 2021).

The Message: Your Chaos Is Your Superpower

The film’s emotional core is Evelyn learning to see her daughter, and herself, not as broken versions of what they should be, but as powerful in ways that rigid structures can’t accommodate. When she finally tells Joy “I would have really liked just doing laundry and taxes with you,” it’s not because laundry and taxes are inherently meaningful, but because she’s learned to find connection and presence even in mundane chaos, rather than constantly fighting to transcend it.

For viewers with ADHD, this message resonates deeply. You are not defective for experiencing the world this way. The problem isn’t your brain. It’s that you’ve been trying to run Linux software on Mac hardware, forcing yourself into operating systems designed for different neurotypes.

The film doesn’t romanticize ADHD’s challenges. It clearly shows Evelyn’s struggles, her failures, the toll on her relationships. But it reframes those challenges from “person broken, needs fixing” to “person in wrong environment, needs accommodation and self-acceptance.” Evelyn doesn’t overcome her nature. She becomes fluent in it.

Conclusion

Everything Everywhere All at Once offers more than representation of the ADHD experience. It offers a philosophy for living with it. The film’s ultimate message is that some minds are designed for chaos, and that’s not a flaw to be corrected but a feature to be cultivated. In a rapidly changing world that increasingly demands cognitive flexibility, rapid context-switching, and creative problem-solving, the ADHD mind’s natural mode may be less deficit and more adaptation.

The conventional approach to ADHD emphasizes creating external structure to compensate for internal dysregulation. The film suggests an alternative: develop internal flexibility sophisticated enough to thrive in external chaos. Not rigid focus, but fluid attention. Not sustained routine, but skillful improvisation. Not everything in its place, but everything in its moment.

For the millions who live with ADHD, watching Evelyn transform from overwhelmed laundromat owner to multiverse-navigating hero offers more than escapist entertainment. It offers permission to stop fighting themselves and start working with themselves. Embrace the chaos, trust your ability to navigate it, and recognize that being everything, everywhere, all at once isn’t a curse to overcome, but a superpower to harness.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Ashinoff, B. K., & Abu-Akel, A. (2021). Hyperfocus: The forgotten frontier of attention. Psychological Research, 85(1), 1-19.

- Barkley, R. A. (2012). Executive functions: What they are, how they work, and why they evolved. New York: Guilford Press.

- Barkley, R. A. (2015). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Hallowell, E. M., & Ratey, J. J. (2011). Driven to distraction: Recognizing and coping with attention deficit disorder. New York: Anchor Books.

- Honos-Webb, L. (2010). The gift of ADHD: How to transform your child’s problems into strengths. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications.

- Knouse, L. E., Zvorsky, I., & Safren, S. A. (2013). Depression in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): The mediating role of cognitive-behavioral factors. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(6), 1220-1232.

- Kwan, D., & Scheinert, D. (2022). [Various interviews regarding Everything Everywhere All at Once]. A24 Films.

- White, H. A., & Shah, P. (2011). Creative style and achievement in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(5), 673-677.

- Wiklund, J., Patzelt, H., & Dimov, D. (2017). Entrepreneurship and psychological disorders: How ADHD can be productively harnessed. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 6, 14-20.